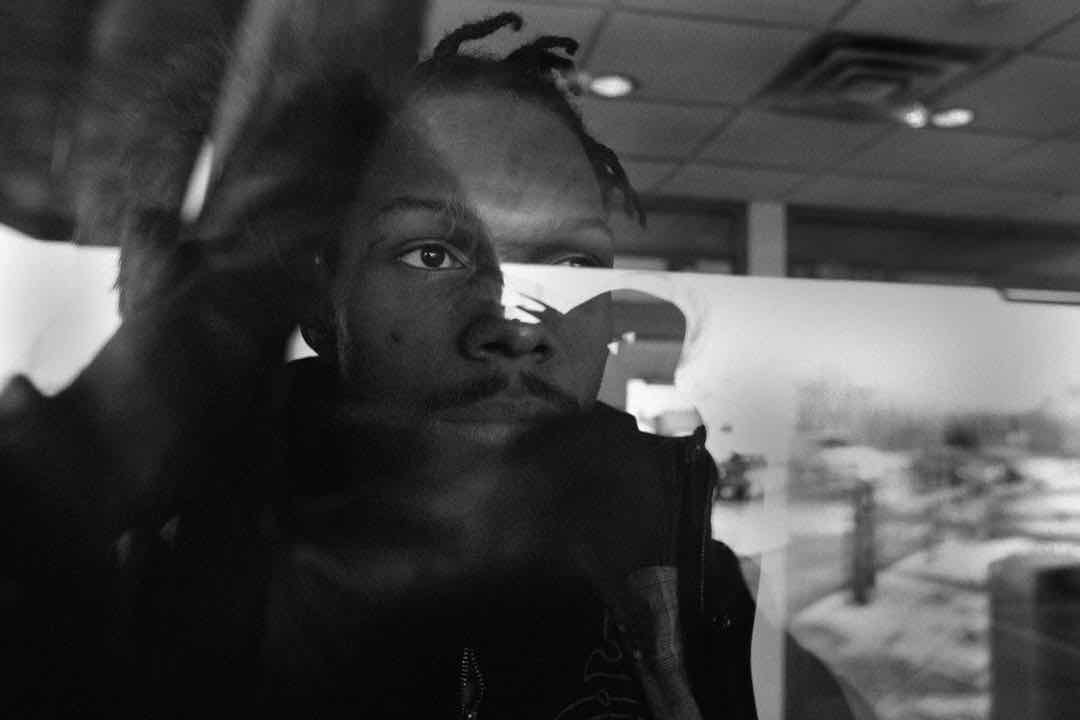

The Grandson of Malcolm X | 1974 - 2013

When you do a piece of investigative journalism, the rules say to never make it personal. But the truth is, stories as an editor you choose to prioritize, stories you choose to put one of your top journalists on, stories you care about and dream about long before you were ever able to make them happen, are always personal.

Going back as far as 2001, I fantasized about what a conversation with Malcolm Shabazz, the only male heir of his grandfather, Malcolm X, would be like. I tried to imagine who the brother might be, a teenager then, living and struggling with the reality of being the tortured progeny of one of the greatest American leaders of our time. What would he look like? What would he sound like? What would he care about?

So when journalist Aliya S. King told me she had “found him” locked up in upstate New York, and that she would write to him and see if we could get an interview, it was one of those rare moments as an editor when you get nervous not because of what you won’t get, but because of what you actually could get.

“Through The Fire,” Malcolm’s first-person narrative as told to Aliya S. King not only became one of my proudest cover stories of GIANT magazine, and the launch exclusive for my African-American focused news site, NewsOne.com, it became a living document of a real life. It was the opportunity for a man to reflect on a personal history shaped first by a parent who witnessed the assasination of their own parent at age 4, and then tragic acts of his own that led to the death of a grandmother.

People often describe me as troubled. I’m not going to say that I’m not. But I’m not crazy...

On the anniversary of his grandfather’s death, I brought Malcolm Shabazz together with renowned photographer Antonin Kratochvil to pay tribute to the Civil Rights hero through a photo story that would emulate the most iconic pictures of El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. The feeling in the room that cold afternoon was eerie. To watch Malcolm put on his grandfather’s shirt and tie, his ring, hat, and, of course, to stage the holding of a rifle in the window—the same image his grandfather staged 40 years earlier—was completely surreal.

Both Malcolms are gone now. His intent when we wrote his story was to begin to live up to the legacy of his grandfather. Now controversies over his death on a Tijuana rooftop may be destined to become as disputed as his grandfather’s was, and likely as conflicted. Let us hope the judgments about the younger Malcolm will be informed by the strongest legacy his grandfather really did leave the world, namely, to always seek the truth.

The tragic death of Betty Shabazz may have been the fault of Malcolm Shabazz, but he should not be vilified for it. The chorus of those for whom social media has given a voice to, who want to anonymously blame Malcolm for not living up to his grandfather’s legacy, or worse, still damn him for the tragedy in that Yonkers home, need to listen to his story. He was 12-years-old. It was an accident. His childhood to that point had been defined by an unknown father and a mother—a troubled figure in her own right—who reportedly struggled with alcohol and mental illness.

All my life I had been shuttled back and forth...never knowing where I was going to lay my head or wake up.

There was also the constant threat of numerous FBI investigations that continued to plague the family long after his grandfather’s death (scurrilous attention Malcolm claimed he continued to receive from federal authorities even up to his last days). And, ultimately, the loss of his grandmother, one of the few family members who had shown him committed love, gave Malcolm a suffering that had never left him.

I didn’t think she would walk through a fire for me...

So rest in peace Malcolm Shabazz. Perhaps the struggles that consumed your life may be as symbolic, in their own way, of those of the man whose life you, too, had to discover through the pages of an iconic autobiography. I’m just glad I got to see you smile.

"Through The Fire" | by Antonin Kratchovil | GIANT magazine

Malcolm Shabazz | behind-the-scenes

Malcolm Shabazz | exclusive interview | as told to Aliya S. King

INTRODUCTION

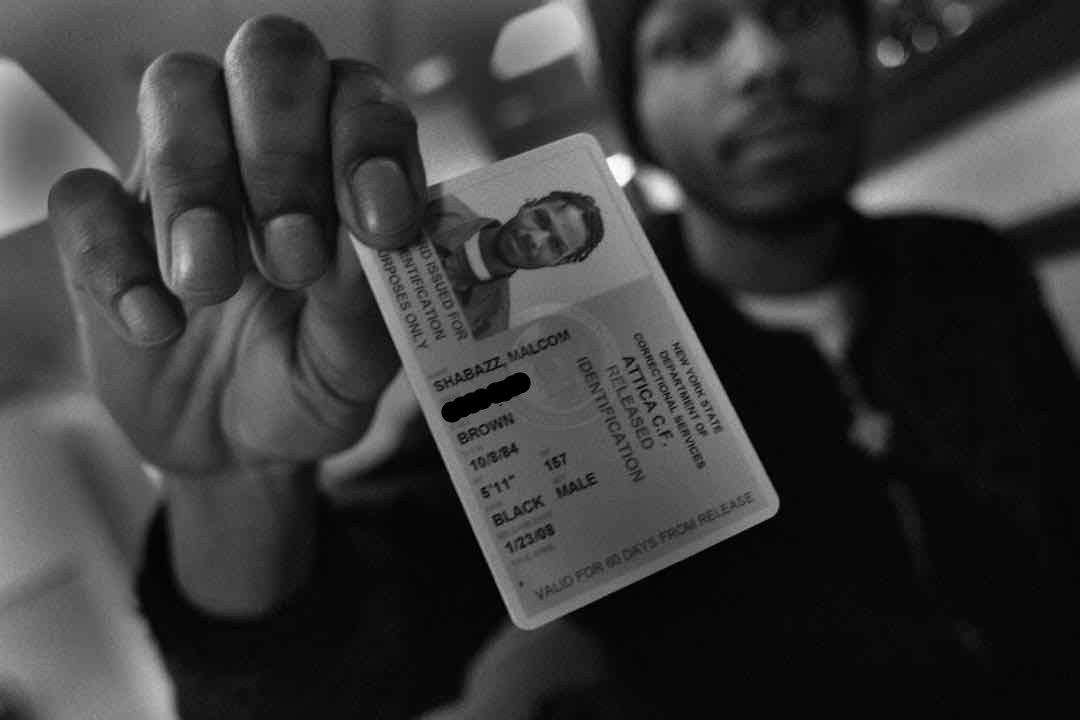

His grandmother, Betty Shabazz, widow of Malcolm X, was killed in a fire he started 11 years ago. He was 12 years old. He had been shuttled in and out of correctional institutions until his release from Attica Prison in February 2007. Now MALCOLM SHABAZZ, 24, is on a mission: to clear his name, stay out of jail and rise from the ashes of his past.

The following are woven excerpts from hours of conversation with Shabazz:

People often describe me as troubled. I’m not going to say that I’m not. But I’m not crazy. I have troubles. A lot of us do. But you need to understand where I’m coming from and why I am the way I am. Considering what I’ve been through, it’s a miracle that I’ve been able to hold it together. I’m just trying to find my way. [I’ve read newspaper stories about me that] say, “Experts testify [that boy] is psychotic.” The way they describe me is wrong — bi-polar, depression, pyro, whatever. I know I'm not at all. Some of the things I've been through, the average person would have cracked.

All my life, I’ve had [moments where] I’ve lived in the lap of luxury in the Trump Towers and not wanted for a single thing. And the very next day I'm [living in] a slum in a gang-infested Philly neighborhood, eating fried dough three times a day. One minute, I’m in a situation with structure and discipline. The next minute I’m running the streets with no supervision at all. One of my aunts has a friend who is very devoted to his children. I was hanging out with them one day and all he talked about was [their] schedule and sports and taking his kids here and there. I wish I had that. I wish I had someone whose purpose in life was to take care of me. That's how white people do it. They plan for [their] kids. We don't. That's cause we don't plan our kids. I wasn't planned.

Malcolm Lateef Shabazz was born in Paris, France in 1984. His mother is Qubilah Shabazz, the second of Malcolm X's six daughters. She was only four years old when her father was killed right in front of her at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. According to her son, Qubilah grew up loving nature and being by herself. When she was still a young girl, she chose to become a Quaker. She later attended Princeton University, but left before graduating. As she told the Minneapolis Star Tribune in a 1995 interview: "I was under a lot of social pressure, largely due to who I was. I did not fit the view of who I was supposed to be. I didn't arrive on campus with combat boots and a beret, and I didn't speak Swahili." After leaving Princeton, Qubilah traveled to Paris, where she began studying at the Sorbonne. It was here that she met Malcolm's father, an Algerian. To this day, her son says he has never met his biological father.

I am [my grandfather’s] first male heir, his first grandson. [I’ve read and been told that] he always wanted a son. No boys in the Shabazz family until me. I used to think [Malcolm X] was my father. My mother told me that. I would ask and she would show me pictures of her father and tell me it was my father. I can't talk to her about him. Nothing in-depth. She acts like she doesn't know about him. She was there. She was four years old and sitting right there [when he was killed]. I don't think she's ever recovered from that.

CHILDHOOD

Qubilah left Paris when Malcolm was still very young and moved back to the U.S. He remembers them moving around a lot, living in such places as Los Angeles and Brooklyn. His mother reportedly took odd jobs at places like Denny's to earn enough to get by.

How do you [fill out an application at] Denny’s and put down Princeton and the Sorbonne as your education? I felt like she was better than that. And I didn’t like seeing [her work those kinds of jobs.] When I was 3 or 4, we lived in California. I used to run away from home. My mother drank and she would be asleep and I would be unsupervised. [According to various news reports, Qubilah Shabazz has had issues with alcohol and mental illness in the past.] I was very adventurous [so] I would walk up [and down] the street. It would end with the police bringing me home. One day I walked to my day care center [which was] miles away. One day I got on the bus and just hung out away from home and no one said a word. Whole day goes by before anyone stopped me. [My mom] loves me. I'm sure of that. Everyone is not meant to be a parent. She didn't hug me. She's just not that kind of person. It used to make me upset and angry [when I was younger].

After California, Malcolm moved to Philadelphia where he lived with his great-grandmother, Madeline Sandlin, the stepmother of his grandmother Betty Shabazz.

She's a very strong woman. Native American—very strong and stern and strict. She [lived] in North Philly. [Her neighborhood] was so rough. It was so bad, I couldn't go outside [and] play. It was like being behind bars. I started school at [a private school outside of Philadelphia]. I went to kindergarten and first grade. These kids were rich. [The bus] wouldn't go to my house. [It] would go to the corner. [The kids] would say, "You live here?" This [white] girl called me a nigger [one time on the school bus]. I didn't even know what it meant. I [just] knew it was something bad. I wanted to be white. They seemed happy, like they had everything they needed. White was equal to happy and rich. And black [was] just the opposite.

My aunt Attallah was visiting [in Philly] one day. I was looking at a magazine and [there was a picture] of a white boy in a suit. [I took the magazine to my aunt] and I said "I wish I was white like this white boy right here." She said, "Why would you say that?"

My great-grandmother couldn’t take care of me forever. I ended up in [upstate] New York living with my teacher for second grade [at the school I was enrolled in]. I liked her--I was calling her "Mom." She had a 16-year-old daughter. I had a pet hamster [and] a bike. I [was] on the Little League team, I [went to] church every Sunday. I had a crush on a white girl named Heidi. I had stability, something I never had before and I liked it a lot. I was the only black kid in the entire school but [I had] a lot of kids to play with. [My aunt] came to pick me up for the summer and I think she didn't like [the situation]. I was happy and taken care of, but I don't think she liked it. She [took me] for the summer [and] as it got closer to September I [kept] asking [if I was going back to Kingston]. She kept saying yeah, but I never went back.

ADOLESCENCE

As Malcolm tells it, he led a nomadic childhood, living at different times with his mother, his grandmother and his aunts.

I was always happiest around my aunt Ilyasah. She always smelled good. I loved staying at her house because she'd always have a tidy home. I loved being with her. She was always funny. One day we were on [an] elevator and I was about to throw up. She cupped her hands up to my mouth like she was going to catch it. When we got off the elevator, I threw up everywhere, all over the floor, all over her hands, but she kept her hands there. That gesture showed how much she felt about me. [It] made an impression on me. I said back then [that] if I ever had a daughter, I would name her after Ilyasah.

[As for] my grandmother, I never saw her relax. She was speaking at colleges [and] going overseas. On vacation, she would take me to a hotel to swim and she would sit there with books and paper. I never saw anyone work that hard. That's why I couldn't live there full time. All [of] my aunts [also] worked a lot [so] I had to shuttle around. That was taught with school. My grades ended up being really poor even though the work was not hard. I wasn't challenged and the teachers couldn't make the connection because I was all over the place.

I started driving when I was 9. I would watch my aunt [Check with writer to determine which aunt] and memorize [each step]. One day, early in the morning I took [her] keys. I had difficulty starting [the car] at first, [but] I drove to school [and] parked [and] went to school like it was nothing. My aunt found out and came to school. They didn't even believe her, but it was true. My mother put me in a mental institution after that. She was really angry. I didn't belong there. I wasn't crazy. I had done something wrong and needed discipline. But not [being sent] to a hospital.

[At the hospital] they start asking me all these questions. [Stuff like] Do you hear voices? I was into Marvel comic books at the time. There were two characters I liked, Mister Sinister [from the X-Men] and the Human Torch. [So] I was like, "Yeah, here's my friend that told me to do it." I just picked them out randomly and drew pictures of them. But I had no idea it would follow me that way it did. I was just making it all up. One time, my aunt came to visit me. She said "You know you don't hear voices. You need to stop." And I did. In my experiences, [the doctors] want to find something wrong with you. That's how they get paid. When I [was in] jail, they said I was depressed and anti-social. I was in jail. I'm in solitary confinement. They gotta say something [is wrong with you].

As Malcolm remembers it, after he was discharged from the hospital, he and his mother moved to Minneapolis, where Qubilah had reconnected with an old schoolmate named Michael Fitzpatrick.

She said she was going for a fresh start and I was excited too. First we [stayed] in a hotel. They would meet there and talk. I heard them talking about Farrakhan. It stayed in my mind, but I didn't really know what they were talking about. I found out later that there were cameras everywhere because there were federal agents watching my mom.

According to published news reports, Fitzpatrick was an FBI informant who helped the agency gather information about an assassination plot against Louis Farrakhan. Qubilah was arrested and charged with plotting to hire a hit man to kill the Nation of Islam leader, who she reportedly believed to have played a part in her father's death. After his mother was arrested, Malcolm was sent to live in a group home and remembers being transferred to foster parents who he claims wanted to adopt him until they learned who his mother was. Qubilah was later cleared of the charges against her, but Malcolm says he didn't see her again for almost two years, at which point she had resettled in San Antonio, Texas.

I went to a boarding school in Connecticut for a while. I lasted there about a month. They went in my property and found a laptop computer that belonged to one of the students on another campus. And they had this kid with a slash in his coat and he said I stabbed him. None of that happened, but my grandmother came and got me out of there. I know she was upset, but we never talked about it. That's how I ended up back in Philadelphia. [When] I was 11, [I] had a fight with a 16-year-old kid. I'm going in so hard, my body goes numb and I couldn't even pick up my arms anymore. I won that fight and [afterwards] I would come out [of my house] and people were different. [They said] "Don't mess with him, he's crazy." [But] I wasn't crazy. I was just scared. I had to adapt to survive.

[My grandmother] didn't know the extent of what I was going through. I told her, but I don't think she believed it. Malcolm was eventually reunited with his mother in San Antonio, where she reportedly worked for a radio station owned by Percy Sutton, who was Malcolm X's attorney before he was killed. She also had a new boyfriend, who Malcolm liked right away.

He would give me hundred dollar bills [for no reason]. And he let me drive his car. We lived in a [nice apartment] with a balcony and a Jacuzzi. My mom was working at the radio station [and I was going to a] private school. We lived in a Mexican neighborhood and everyone made a big deal that I was from New York. [When you're from New York] all the girls like you [and] all the dudes hate on you. I got kicked out because my mom started drinking again. [And] her boyfriend ended up going to jail for an attempted murder [charge]. [Suddenly,] there was no food in the house. She's not taking me to school [so] I'm falling behind. She wouldn’t get up to take me to school and I started falling behind. [One morning,] I woke her up to tell her to take me to school. She got belligerent. She tried to bite me. And I pushed her. She said I hit her, but I didn't. She put me in a mental hospital for two weeks.

After that incident, Malcolm says he was sent back to New York, even though he wanted to stay with his mother.

All my life, I had been shuttled back and forth, living with this [person] or that [person], never knowing where I was going to lay my head or wake up. I was so sick of it. I wanted to be back with my mom. [The day I came back to New York] it was cold and rainy. My grandmother came to pick me up [at the airport]. I had the big skater pants [on] and the earring. My grandmother said, "Can we please get you to stop wearing those pants?" [After that] I started acting out. I was doing a lot of things--I was stealing money from my aunts to save up to buy a ticket [back to Texas].

THE DEATH OF BETTY SHABAZZ

In the middle of the night on June 1, 1997, authorities responded to a fire at Betty Shabazz's residence in Yonkers, New York. According to reports, Malcolm X's widow sustained burns over 80% of her body. Her grandson was held under suspicion of starting the blaze. On June 23, after several operations in the hospital, Betty Shabazz died. She was 63 years old. On July 10, Malcolm, then 12, pleaded guilty to the juvenile equivalent of manslaughter and arson. He was sentenced to 18 months in a juvenile facility for troubled adolescents. He remained in state custody for almost four years. In April 2001, he was sent home with an electronic monitoring device, but soon ended up back in detention due to curfew violations. In January 2002, he was arrested in Middletown, New York on robbery and burglary charges. That September, he was sentenced to 3½ years in prison. He received parole in May 2006.

I didn't mean for my grandmother to get hurt. I wasn't thinking anything like that would happen. [I thought] she would go to the fire escape [but] she walked through the fire to get to me. I didn't think she would walk through a fire for me. People say [to me] "Oh you are the one who burned down your grandmother's house?" [But]...it didn't really happen like that. I've always told the same story. [I was] coerced to say something else, because [I was told] it would be better for me. [I was told] I would go to jail forever...